Terrell-Havens-Terry-Ketcham Inn

81 Main Street, Center Moriches, New York 11934

Samuel Terrell, a blacksmith, constructed a timber frame one-room structure on this site in 1693. Subsequent significant additions enabled the building to become a 15-room inn used as a tavern, public house and stagecoach stop by the Havens, Terry, and Ketcham families.

Benjamin Havens ran the Inn during the Revolutionary War. He is believed to have been a member of the Culper Spy Ring because he had strong connections to the network. He was married to Abigail Strong of Setauket, sister of Patriot leader Selah Strong and related to Culper chief spy Abraham Woodhull through her mother, Suzanna Thompson. In 1791, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison stayed at the Inn on their way to visit William Floyd at his estate in Mastic.

Samuel Terry (c. 1800) and his son Nelson owned the Moriches Inn. In 1851, Andrew Ketcham bought the farm and Inn. Townsend Valentine Ketcham (son of Andrew) and his wife Matilda ran the Inn until 1914. Andrew Watson Webb Ketcham managed the tavern after his brother Townsend’s passing, until the Ketcham heirs Ella May and Mary Zoretta sold the property in 1918 to Gilbert H. Loper and Bartlett T. Ross.

Subsequent owners used the structure as a tea house, a residence, a restaurant, and a boarding house. In 1989, the structure, with years of neglected maintenance, was damaged by a dining room fire. That same year, Ketcham Inn Foundation, Inc. was formed which bought the property and proceeded with a ground-up timber frame restoration of the structure to its historic colonial appearance. On March 9, 1992, the Terrell-Havens-Terry-Ketcham Inn was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Long Island History Project Interview, Episode 62: Bert Seides and the Terry Ketcham Inn

Bertram E. Seides, President Ketcham Inn Foundation Inc, speaks about the process of obtaining the Ketcham Inn and raising funds for restoration. Mary E. Field, Moriches Bay Area historian, speaks about her book she wrote with her husband, Van R. Field, historian and genealogist, “The Illustrated History of the Moriches Bay Area.” Bertram E. Seides and Mary E. Field interviews were conducted at Dowling College.

KETCHAM INN HISTORY

Written by Patrick Mealey & Joyce Jackson, 2010

With the Thanksgiving holiday approaching, I got a hankering for old friends and old haunts. We decided to embark on a visit to the other Eastport; the one on Long Island’s East End, just west of that enclave of wealth and celebrity – the Hamptons. Though the whole area has experienced a revolution in sometimes distressing upscale development in recent years, Eastport still manages to cling to some of its old time rural charm.

Known in the first half of the 20th century as the “Duck Capital” of the world, the compact little hamlet was the center of the production of that Long Island bird, producing 6.5 million annually from 29 farms. In the last two decades, most of these farms have gone the way of Maine’s sardine industry, with descendants of the original farmers selling valuable waterfront property to eager residential developers.

The plan was to have Thanksgiving dinner with a close friend/member of the family, in her live-in, Main Street, fine art gallery.

While in the area, we availed ourselves of the opportunity to accept an invitation from our friend, Bertram Seides, in nearby Center Moriches and pay yet another visit to what has become his magnificent obsession, the Havens-Terry-Ketcham Inn.

It was Bert, a Center Moriches native son, architect and ardent preservationist, who in 1989, realized that there was an important local landmark in danger of the wrecking ball. He organized a grass roots effort to rescue the ailing structure. Since then, Ketcham Inn Foundation, under his passionate direction, has been mounting a painstaking restoration of the venerable and historic old building.

Patrick remembers, in the early 1990’s, driving down Old Montauk Highway and passing the forlorn, sagging, somewhat barn-like, cedar shingled building and thinking “that place looks really old.” He wondered who owned it and what was to become of it. Then one day in a 2001 drive-by, we noticed a number of large steel I-beams, spaced evenly, jutting out just under the second floor.

Someone was planning to lift the tired old structure up.

It would be several years later, after a permanent move to Perry, Maine, before we would have the opportunity to return to Long Island, meet Bert through our Eastport friend, and finally learn the story of the ancient edifice.

Little was known of its age or history when efforts began to save it, but diligent scholarship, archeology and analysis has changed all that. The building is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Originally called the Moriches Inn in Brookhaven town records, the building has served as a tavern, inn and public house. The oldest portion, appears to be a settlement cottage and dates to the late 1600s, a time before the area was officially settled. Subsequent additions followed over the next one hundred years (with a kitchen wing added in the 1940s), bringing the building to its present configuration.

No – George Washington never slept there, but Thomas Jefferson and James Madison did.

The property was part of a tract of land (Warrracta Neck), owned in its early days by Samuel Terrill, a blacksmith from Milford Connecticut. He purchased the parcel from Jacob Doughty of Jamaica in Queens County in 1698. To keep on friendly terms with the indigenous Paquatuck, it was said, Chief John Mayhew was at one time paid “a competent sum of money for the land.” Terrill, whose wife may have been Native American, was known to have good relations with the local tribe, who named a nearby river in his honor. Early accounts suggest a fire destroyed his homestead and blacksmith shop on the west shore of the Terrill River. He sold the property to Sarah Scudder Conkling in 1714 and moved to nearby Yaphank Neck, another of his holdings.

Sarah was the widow of John Conkling of Southold on Long Island’s North Fork. John died about 1705, leaving his wife and their two sons, John and Henry, a sizable amount of money and property in Southold. Sarah established a cattle ranch on the former Terrill property; most likely for trade with the West Indies. Her land passed to her son, Thomas, after her death in 1753. Thomas quickly sold to his sister, Sarah’s, son, John Havens Jr. Sarah’s husband, John Havens Sr., formerly of Shelter Island, passed away in 1750 leaving his holdings to his sons. By 1770, John Jr and his brothers, Benjamin and Henry, owned almost all of the land between the Terrill River and the Forge River in Mastic.

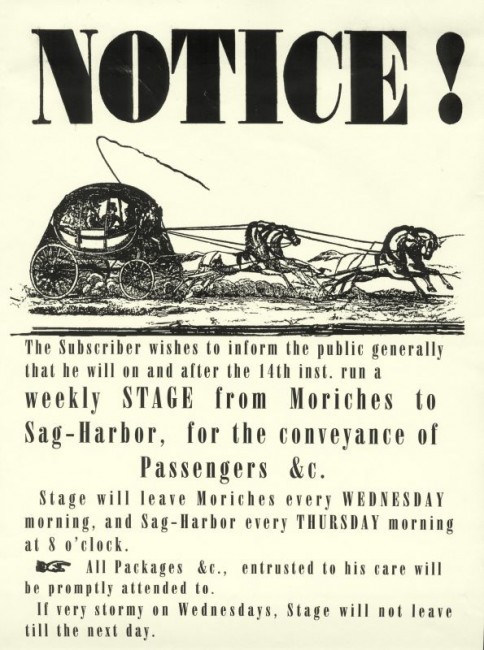

It was Benjamin Havens, who proposed in 1772, along with several other innkeepers, a coach route (King’s Highway), from Brooklyn to Sag Harbor that made a stop at his inn in Moriches. It is the earliest such route to traverse Long Island.

He was known to have run a tavern at the inn during the Revolutionary War while the British occupied Long Island. Too old for service, Havens assisted the Patriot cause by spying on the British troop and supply movements in and around nearby Fort St. George; a fortified Loyalist outpost and storage depot. In 1780, the Continental Army led by Benjamin Tallmadge, mounted a successful raid across Long Island that culminated in the Battle of Fort St. George. The British, who at one point raided Haven’s inn, referred to Benjamin as a “most pernicious caitiff.”

In 1775, Captain John Hulburt stayed at the inn with his troops on their way back to Bridgehampton from the pivotal Fort Ticondoroga following a campaign to liberate the Champlain Valley. After the revolution, founding father and New York State’s first governor, George Clinton, also stay there. He would later become Vice President, serving under both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

By 1791, Havens sold to William Terry who also ran it as an inn. It was in 1791 that Jefferson and Madison stayed at ‘Terry’s Hotel’ while visiting prominent Long Islander, General William Floyd in nearby Mastic. The seat of the federal government was in New York City at the time and Jefferson was George Washington’s Secretary of State. He and his friend, Madison, were on Long Island investigating a plague of Hessian flies that were doing great damage to the American grain industry. While in the area he was also documenting the vanishing Native American languages. The inn would serve as ‘home base’ while he made records of the Unkechaug language, when visiting the Poospatuck reservation in Mastic.

Terry descendants sold to Andrew Ketcham of Huntington in 1852. In the Ketcham era the inn’s central location provided for a variety of public gatherings. It was used for voting and the local court was held there. During the Civil War, volunteers would meet and drill on the property. Traveling merchants, dentists and doctors stayed there while they sold their goods or tended to the local community. The inn remained in possession of the Ketcham family until 1912.

With monikers like Clinton Inn, Wayside Inn, Hitching Post, Colonial Arms and Stage Coach Stop, the inn would remain in continuous use in one form or another until August of 1989. It was at this pivotal moment that an unfortunate, destructive, though contained fire, would ignite efforts and set the stage, like the mythical phoenix, for the landmark’s eventual rebirth.

On the first day of December, 1698, just a month and a half after purchasing a large tract of land known as Warracta Neck, the blacksmith, Samuel Terrill, suffered a calamity so severe that it would leave himself and his family homeless.

A fire kindled in the thatch of his home “consumed to ashes” his “house together with all his goods, clothes & provisions.” Thankfully, his wife and six small children were spared. His neighbors recognized his “great poverty and necessity” and Samuel then himself, petitioned the governor of New York to grant him “authority for the collecting and receiving the charity of well disposed persons.”

Nearly 300 years later, on a Thursday, August 3, 1989, 23 individuals, adult and children, residing in a homeless shelter in Center Moriches would fall victim to a similar event.

Started by a 12 year-old boy, about 3 A.M., the fire would quickly spread from a couch in the first floor dining room to the second floor, involving much of the front of the house. Terrified residents, forced to leave their belongings behind, were sent fleeing into the night. Fortunately a smoke detector connected by phone directly to the fire station summoned help, which came promptly. This crucial element would minimize damage and prevent loss of life. The traumatized and distraught residents were found alternative housing within hours of extinguishing the blaze.

At the time of this unfortunate incident, homeless shelter was just the most recent incarnation of a building whose earliest wing may well have been standing, when Samuel Terrill and his family found themselves ‘on the street.’

What could have been the death knell for the ancient edifice became a call to action. The old inn was left in poor condition and demolition seemed eminent. The absentee owner was contemplating tearing the structure down, so that he could sell the property for a shopping center. A small group of local concerned citizens were granted permission to clean up the site and research the building’s historical and architectural significance. The Ketcham Inn Foundation was born.

When we were first privileged to meet the organization’s tireless leader and take our inaugural tour of the inn’s restoration, we found in Bertram Seides, a kindred spirit. We shared stories of our own restoration efforts as he shared his. We began to learn the inn’s compelling story. His enthusiasm for the process, down to the most subtle of minutia, was refreshing. Anyone who has ever taken on such an ambitious project knows that none of it is easy.

We were pleased to find out how much had been accomplished in the intervening years since that unhappy conflagration. The site was finally protected and lay in an historic district. Archeology had been done, conservation specialists had been brought in, plans had been drawn, history had been gathered and restoration carpenters specializing in timber frame construction had been hired and were busy on the job. Extensive work had already been done to peel away the layers and identify and preserve what was original to the historic building.

Though scorched evidence of the fire was apparent, we were surprised to see how much early material had endured the event – remarkably unscathed. A corner cabinet, mantles, wainscoting, trims around doors and windows and the structure’s re-exposed overhead beams were just some of the surviving elements.Though much antique plaster had crumbled away, the building’s ancient ‘accordion’ lath remained. Bert showed us how severely damaged elements were being carefully documented, then replicated with appropriate materials by expert craftsmen.

Restoration usually begins with stabilization and the bones of this building needed some serious tending to; the pretty parts would come later. Three centuries of occupation along with occasional periods of neglect had taken their toll. Bert explained how the structure had been lifted (those steel I-beams we recalled), so that the sill and floor joists as well as the old foundation could be restored. Solid oak was put in place by the Foundation’s skilled timber framer where original structural elements had failed.

An old building retains many clues even if early parts are missing. Bert pointed out ‘tells’ in the structure around the windows indicating that most of the window frames were 19th century replacements for 18th century originals. Surviving elements of an early frame would be used as a template to recreate the older form. Everything was carefully documented and labeled – though it seemed that you didn’t really need to – Bert could always put his hands on exactly that piece his carpenter was looking for and knew right where it belonged.

On a subsequent visit the failing east chimney was being restored (actually rebuilt from the ground up) and the attic was being stabilized and prepped for a new roof. Several years later we returned to find new cedar shingles fully in place with the recreated chimney again on top. The circa, 1690s back wing’s exterior was also restored, only awaiting an archeological dig (we hope to participate in) before the 17th century fireplace and interior can be reconstructed.

This most recent visit, just a year since our previous walk through, saw further substantial progress. We entered the Foundation’s office to find Bert and his sweet mother stuffing envelopes for the yearly newsletter and financial appeal. Thankfully, the ongoing challenge of fundraising has to date been sufficiently successful to keep the project moving.

Bert says that he is beginning see the light at the end of the tunnel. The west elevation has been re-shingled (the historic exposure respected) with new red cedar shingles fastened with reproduction square nails. Authentic details were reproduced – like lines scored with a scribe on each shingle for accurate nail placement. Also imitating the originals, these lines will only become more pronounced over time as the shingles weather. Recreated oak window casings to match early examples have also been installed with period window sashes still on the way. These sashes will be crafted, mostly by hand, using antique planes to form their 18th century profiles. Plans are in the works for substantial reconstruction to the front elevation and porch in the coming year.

Interior restoration continue to progress at a rewarding pace. This trip we finally had a chance to meet restoration carpenter, Scott Brown, who was busy with a variety of interior projects. Bert pointed out Scott’s masterful ‘dutchmen’ that were here and there – patching holes in floors, baseboards and where electric sconces once hung over the fireplace. Complex grain matching seems to be his specialty.

Scott and his son had just pulled up sheets of plywood that had been covering the original ballroom floor for 75 years – an exciting moment for everyone; to see the old dance floor boards for the very first time since the start of restoration. This event reminded me of an anecdote that that Bert told on an earlier excursion. As the ball room was on the second floor and not sufficiently sturdy to carry the weight of a ‘frolicking’ clientele – the innkeeper would prop up the floor from underneath with temporary wooden posts in preparation for a big dance upstairs.

It seems fitting that the building was most always a public space hosting travelers by stage coach (later by rail), providing shelter for the night, drinks in the tavern, dances in the ball room and dinners in the restaurant. This historic site will again have a public purpose, as a living museum and farm (for children and adults), reflecting life in the Moriches area the 18th and 19th centuries.

Before leaving that day, we took a minute to pay a visit to two nearby timber frame buildings, an 1850s hay barn and 1770s carriage house, both of similar size and form to 19th century originals that once stood on the site. These donated farm buildings have been erected on the exact locations those early structures once occupied – their footings determined by archeology. The combined barn and carriage house creatively serve as a space for the Foundation’s – Book Barn. Whether you find a book that day or not – you will definitely come back for another look after meeting dedicated volunteer and local historian, Mary Field, who can often be found ‘manning’ the shop.

Mary and her husband Van have written several books together including, The Illustrated History of the Moriches Bay Area and Nettie Ketcham Diary. The Fields have worked tirelessly researching the inn’s long history. Van, who served for 18 years as the foundation’s vice-president, passed away in 2007 – reminding us that our affection for an old building has everything to do with our own mortality.

We left Long Island feeling more connected and grounded to our own neck of the woods – inspired by the patience, perseverance and dedication we’d seen. With so many precious historic structures vanishing everyday – we’re glad to know that the Havens-Terry-Ketcham Inn remains under the watchful eyes and care of such vigilant and visionary stewards.

The organization is always looking for furniture, ephemera and other items that actually once graced the old inn. The circa 1850s Ketcham voting box, displayed in the Foundation’s office, always catches my eye. There are already many donated antiques in storage that will eventually furnish the space.

Annual Ketcham Inn Fundraisers:

Tours are available